| Musings About Treating Laminitis Stephen E. O’Grady, DVM Laminitis can be a devastating disease, is able to cause extreme pain, often results in the loss of an athletic career and/or future soundness, is difficult to treat, often presents a variable response to treatment and ultimately can result in the loss of life. Few diseases are more frustrating to veterinarians and farriers than treating equine laminitis. While speaking at a seminar in California in 2000, I remember this quote from Dr. C.W. McIlwraith, ‘Laminitis remains the most controversial disease in equine veterinary medicine with regards to etiology, treatment and prognosis’…still true today! Other than work on the pathophysiology of laminitis, research has yielded little new clinical information on treating this disease. The equine foot is the one aspect of equine veterinary medicine that generally requires input from two professions…the veterinarian and the farrier. This relationship often complicates the treatment of laminitis through misunderstandings, opposing treatment protocols and controversy. Why is laminitis hard to treat?

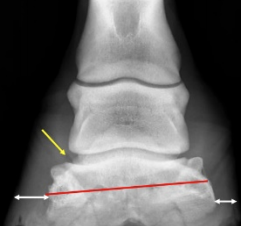

Prefaces I use three prefaces as a prelude to teaching seminars or discussing protocols with clients to explain some of the complexities associated with treating laminitis. Preface # 1. It is the extent of the lamellar pathology that will limit the success of treatment and not the treatment regimen itself (O’Grady 1999). The cause of the laminitis and the progression of the disease in the first few days may give some indication as to the damage to the lamellae and a prognosis regardless of the treatment. Laminitic cases that show distal displacement (sinking) have circumferential damage to the lamellae and the sheer weight of the horse displaces the bone in the hoof capsule. In the process of sinking, the horn  tubules at the coronet are bent and presently, we are not able to straighten the horn tubules /papilla to produce hoof wall. We are all humbled by the odd case but generally these cases do not respond to treatment due to the extensive damage to the lamellae. tubules at the coronet are bent and presently, we are not able to straighten the horn tubules /papilla to produce hoof wall. We are all humbled by the odd case but generally these cases do not respond to treatment due to the extensive damage to the lamellae. Preface # 2. Treatment regimens for acute and chronic laminitis remain empiric and are based on the experience of the attending clinician (Hunt 2001). Veterinarians and farriers generally have a favorite type of farriery for laminitic cases. For example, it’s human nature that if one is successful treating a few cases with treatment X, the next few cases will also be treated with treatment X. There are a myriad farriery options and farriers tend to have their favorite method, many specialty shoes / appliances are purported to be successful on all cases and clients are continually influenced by the internet. Laminitic cases should be treated on an individual basis using farriery principles which include redistributing the load on the solar surface of the foot, repositioning breakover and providing heel elevation (when necessary) to decrease tension in the DDFT. Whatever shoe or appliance selected must be combined with the appropriate trim to be successful. Preface # 3. Treatment is further complicated by the fact that there is no proven or consistently successful treatment for laminitis (Moyer 2000). There is a plethora of farriery options for treating acute and chronic laminitis. However, it is safe to state that controlled studies comparing the efficacy of one farriery technique to another simply does not exist. With this in mind, when treating a severe case of laminitis, it is prudent for the veterinarian and farrier to discuss with the owner/trainer from the onset, that the farriery selected is based on our experience but by the very nature of the disease, the outcome is not predictable. I have found setting a timeline to be useful and barring unforeseen complications; assess the progress following an agreed upon period and decide whether to continue or decide whether to stop. What’s new… If I look back over the last twenty years at what has changed in my clinical practice, the following come to mind… The use of ice For years, the use of ice in the developmental stage of laminitis was shown to prevent the clinical manifestation of the disease (Pollitt and Van Eps 2004). However, In clinical practice, it is not easy or sometimes practical to identify those horses susceptible to coming down with laminitis. In a recent paper, the use of ice in the acute stage appears be an effective therapy in certain cases to halt or decrease pathology in the lamellae (Van Eps and Pollitt 2016). To be effective, the ice should be used as an ice slurry from above the fetlock to the ground continuously for the first 48-72 hours. Using two radiographic views For as long as I can remember, the lateral radiographic view was the ‘gold’ standard for evaluating / treating laminitis, but it did not allow for identification of asymmetrical medial or lateral distal displacement. The lateral view only looks at the position of the distal phalanx within the hoof capsule in the sagittal plane. Adding a dorsopalmar 0°DP view notes the position of the distal phalanx in the frontal plane. Combining the two radiographic views allows the clinician to assess displacement of the distal phalanx in both the dorsopalmar and medial lateral planes. Previously, many treatments failed because the DP view was not available or being assessed (Parks 2007). Unilateral displacement of the distal phalanx  The DP radiographic view identifies unilateral displacement of the distal phalanx, permits earlier farriery intervention and in many cases, the farriery can be modified due to foot conformation as a preventive measure. In my practice, I have not seen a case of unilateral displacement in the forefoot where the distal phalanx was not offset to the lateral side which places more load on the medial side. If I see this type of foot conformation or radiographic signs of displacement, I have been successful by modifying the farriery to move the center of pressure CoP toward the lateral side of the foot. If the coronet ruptures on the affected side, treatment is usually not effective. The DP radiographic view identifies unilateral displacement of the distal phalanx, permits earlier farriery intervention and in many cases, the farriery can be modified due to foot conformation as a preventive measure. In my practice, I have not seen a case of unilateral displacement in the forefoot where the distal phalanx was not offset to the lateral side which places more load on the medial side. If I see this type of foot conformation or radiographic signs of displacement, I have been successful by modifying the farriery to move the center of pressure CoP toward the lateral side of the foot. If the coronet ruptures on the affected side, treatment is usually not effective.The wooden shoe  Understanding the biomechanics of the wooden shoe along with a working knowledge of good basic farriery are essential for consistent success. This would include the appropriate foot trim, proper size, fit and placement of the wooden shoe on the foot combined with the appropriate application. See here. Case selection to use the wooden shoe is important and excludes laminitis patients deemed to have a poor prognosis. Horses selected in the writer’s practice, although often painful, are judged to have sufficient integrity of the hoof structures in which to apply the appropriate trim and use the biomechanical aspects of the wooden shoe to get improvement. Understanding the biomechanics of the wooden shoe along with a working knowledge of good basic farriery are essential for consistent success. This would include the appropriate foot trim, proper size, fit and placement of the wooden shoe on the foot combined with the appropriate application. See here. Case selection to use the wooden shoe is important and excludes laminitis patients deemed to have a poor prognosis. Horses selected in the writer’s practice, although often painful, are judged to have sufficient integrity of the hoof structures in which to apply the appropriate trim and use the biomechanical aspects of the wooden shoe to get improvement.Steroids and laminitis There are papers cited in the literature that state the evidence for corticosteroids inducing clinical laminitis are lacking or inconclusive (McClusky and Kavenagh 2004; Cornelisse and Robinson 2011). However, from the author’s experience and data base, there appears to be a correlation between steroids and laminitis. In my opinion, coupled with a systemic or intra articular dose of corticosteroids, there seems to be additional criteria necessary to induce the disease: firstly, a very fat or obese unfit horse and secondly, some type of stressful event. The problem is that it is difficult to identify these at-risk cases. However, we can identify not-yet-laminitic insulin resistance horses via phenotype & insulin/leptin testing as well as not-yet-laminitic PPID cases via phenotype & ACTH assay. When to stop The question as to when to discontinue treatment for a severe laminitic case always brings up humane and ethical issues. Looking at the humane aspect, it is irresponsible to prolong the life of a chronically painful horse that has no chance of recovery or any future quality of life. The decision for euthanasia is often subjective, and the clinician must take into consideration the owner's psychological attachment to the horse. Monetary and insurance considerations must be discussed, frankly. Convincing evidence can and should be presented to the owner, such as duration of the current treatment, status of the horse (unrelenting pain, recumbency, pressure sores or weight loss), foot conformation (no hoof wall or sole growth, prolapse of distal phalanx through the sole, or a palpable trough at the coronet), and imaging (severe displacement, rotation and/or sinking, position of coronet, or irreversible damage to the hoof capsule). If a decision is reached to euthanize the horse, the decision should be unanimous among all the members of the team. The clinician should recommend, encourage, and facilitate the owner to seek a second opinion if any doubt remains. The attending or consulting veterinarian or farrier should never imply to the owner that a different approach or mode of therapy initiated at a particular time would have changed the outcome of the case. There is no scientific evidence to support such a derogatory statement, it casts doubt on the professionalism of the clinicians involved, and it opens the door for possible litigation. It is unlikely there will ever be a single drug or other line of therapy to treat laminitis… think prevention! Be Safe |