The Wooden Shoe - Farriery has so many optionsReprinted with permission from Farrier Products Distribution |

1a. |

1b. |

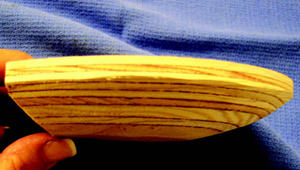

| 1a. and 1b. A horseshoe with a broad toe is used as a template. Cut out the wooden shoe in the shape of a horseshoe using an angle saw or it can be cut and modified using carpentry or farriery tools to provide the appropriate bevel. |

One of the amazing aspects of the farrier profession is that there are so many practical options available to the farrier when an alternative to a horseshoe may be necessary. The wooden shoe has become a practical and very effective option in my practice for treating not only chronic laminitis but many other foot problems. Among the other foot problems that may benefit from the wooden shoe are extensive white line disease, fractures of the distal phalanx / navicular bone and an immediate increase in sole depth when applied to horses that have feet with thin deformable soles. With chronic laminitis and these other foot problems, the wooden shoe is only used as a transitional device to promote hoof wall growth at the coronet and increase sole depth. Once the necessary hoof mass is present to achieve stability and realignment of the distal phalanx within the hoof capsule, conventional farriery is again used or the horse can be left barefoot. To be effective, the farrier needs to understand the principles of the wooden shoe in order to use his or her skills to apply the appropriate foot trim combined with the fabrication, proper placement and application of the shoe. The wooden shoe is simple to apply, but as with any procedure, there is a learning curve, so chronic laminitis will be used as an overview or example of the procedure.

There are 3 basic mechanical principles that are used to treat chronic laminitis:

2 |

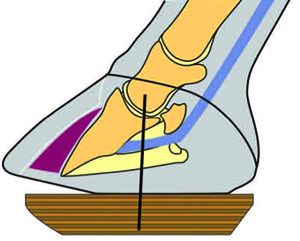

| Illustration shows the ideal trim using the radiograph as a guideline. Note the placement of the shoe. Black line denotes the center of rotation. |

3 |

| Wooden shoe placed on foot with chronic laminitis. The last screw placed against the hoof at the heel is termed a 'strut.' Note the black line is the widest part of the foot. Red line is drawn from the dorsal coronet to the ground denoting breakover. |

4 |

| 2 inch casting tape is placed around the perimeter of the shoe/foot incorporating the screws to add security and provide circumferential stability to the foot. |

The wooden shoe has all the mechanical components of other farriery systems previously advocated for the treatment of chronic laminitis yet it may possess some additional advantages over previous methods used. A major advantage of the wooden shoe is its ability to concentrate the load (weight) evenly over a specified section of the foot due to its flat solid construction1, 2, 3.

Other advantages include:

Materials such as wood or layered plywood are used to create the shoe. A horseshoe with a broad toe is used as a template to cut out the wooden shoe in the shape of a horseshoe using an angle saw or it can be cut out and then modified using carpentry or farriery tools to provide the appropriate bevel. A bevel of 45° is created around the perimeter of the shoe which helps negate the ground reaction force (GRF) exerted on the lamellae (Figures 1a & 1b on page 1).

A radiographic study consisting of a lateral and DP view are essential to determine the position/displacement of the distal phalanx within the hoof capsule and the radiographs are then used as a guideline for farrier trimming. Using the widest part of the foot as a landmark, the heels are reduced from this point palmarly (toward the heel) according to the radiographs and the toe is backed up from the dorsal hoof wall. Following the trim, the hoof wall at the heels and the frog should now be on the same plane. The shoe is now fitted to the foot; impression material is placed in the frog sulci and over the frog if necessary to create a solid flat plane across the heels. The shoe is attached to the foot using thin drywall screws placed in pre-drilled holes through the hoof wall located behind the widest part of the foot and the horse is then allowed to stand on the shoe to disperse the impression material in an even manner. A rasp is used to form a vertical line extending from the dorsal coronet to the ground to determine the point of breakover. Using a rasp, the bevel at the toe is extended back to this point to create the desired breakover. Additional screws can be placed against the hoof wall around the perimeter for stability and to act as 'struts'. Finally, 2 inch fiberglass casting tape is placed around the perimeter of the hoof wall and the wooden shoe which encompasses the screws and the struts to further secure the shoe and provide circumferential hoof wall stabilization (Figures 2, 3, 4 & 5).

5. 6a. 6b. |

| Left (5): Lateral radiograph showing placement of wooden shoe and point of breakover. Black line is center of rotation and red line is point of breakover. Center (6a): Kerckhaert Steel Comfort shoe used to transition out of wooden shoe. Note the breakover has been modified further. Right (6b): Kerckhaert Steel Comfort shoe placed on foot. The flat surface of the wedge insert is used to create even pressure across the hoof wall at the heels and the frog. |

The shoe can be further modified to unload painful areas of the sole or if the sole has dropped or prolapsed by recessing the shoe's solar surface. Shoe modifications are easily added or subtracted (i.e. rasping the toe of the shoe to adjust breakover), with the foot in the farrier position. The wooden shoe being malleable will often be modified by normal wear which allows the horse to find a comfort zone unique to its individual needs.

Post application, the horse is radiographed at 4-5 weeks to determine hoof wall growth and sole depth. Depending on the increase in structural mass, the shoe can be left on longer, reset once more if necessary or changed over to a conventional horse shoe. The DDFT musculotendonous unit will shorten due to the rotation and it will further accommodate/adapt to the heel elevation provided by the wooden shoe. This must be taken into consideration when transitioned back to a traditional shoe as the heel elevation needs to be lowered gradually. After the appropriate trim, most any steel or aluminum shoe can be modified to provide the necessary mechanics. I often use a Kerckhaert Steel Comfort shoe with the toe modified further for enhanced breakover and a 2° or 3° wedge insert to provide the necessary heel elevation. The heel elevation is reduced on subsequent resets (Figure 6a & 6b).

Various farriery methods have been described for treating chronic laminitis, yet no particular method has become the preferred choice. The wooden shoe may possess certain advantages over existing methods such as redistributing the load evenly over the palmar/plantar section of the foot due to its flat solid construction and the mechanics (beveled perimeter, breakover and heel elevation) that can be incorporated directly into the fabrication of the shoe. It should be apparent that the advantages of this farriery option will also be limited unless strict attention is paid to the details involving radiology, foot preparation and application of the shoe.

References