How to Surgically Access Lesions Beneath the Hoof CapsuleReprinted with permission from the American Association of Equine Practitioners. |

|

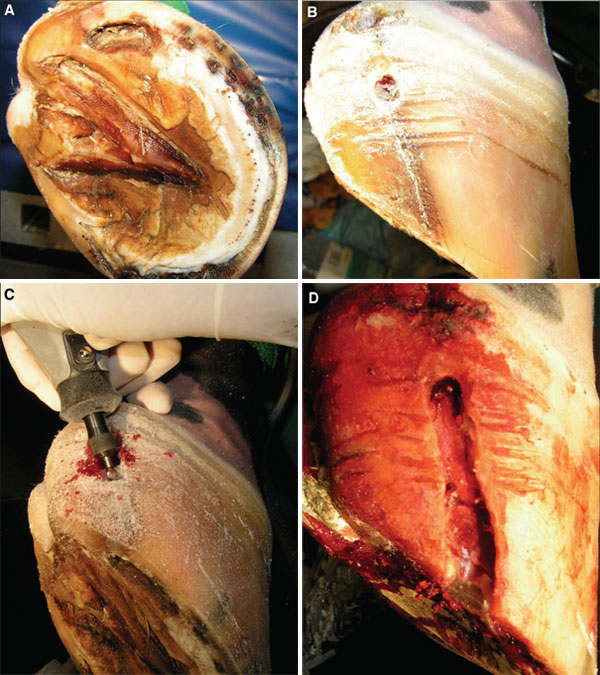

| Fig. 1. Chronic hoof crack for >2 yr that intermittently caused severe lameness as a result of underlying infection. (A) Solar view. (B) Lateral quarter. The unattached hoof wall surrounding the crack was removed with (C) a motorized burr until (D) healthy attached margins were encountered. |

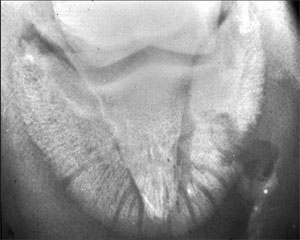

The clinical signs that would alert a practitioner to the possibility of a sequestrum would include a history of chronic lameness, recurrent purulent drainage from the sole, and the presence of a draining tract that leads to bone. Radiographic evidence of osteolysis or sequestration of a bone segment is definitive for this condition. Occasionally, osteolysis, not a sequestrum, is identified, which is evidenced by irregular margination and loss of normal bone density. Either of these radiographic presentations (osteolysis or sequestrum) is evidence that surgery is indicated. The infection generally affects the soft tissues of the sole, laminae, and hoof wall as well as the distal phalanx.

Treatment is aimed at surgical debridement of the affected bone and surrounding soft tissues. The goals of surgery are to provide drainage of purulent exudates, debride infected soft tissue, and remove devitalized bone.

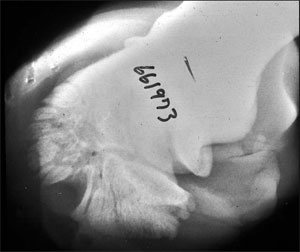

Surgery can be performed with the horse anesthetized or standing. The authors typically debride the distal phalanx with the horse standing and the foot blocked. A tourniquet applied around the fetlock to compress the digital vessels against the proximal sesamoid bones will greatly facilitate visualization during surgery. The cornified sole surrounding the draining tract can be removed with a hoof knife, motorized burr, or in some instances, a scalpel. The laminae between the cornified sole and distal phalanx is removed by sharp dissection, and the draining tract is followed to the bone. Infected bone is softer than normal bone, which is removed with a large-basket spoon curette. The soft tissue and bone are curetted to healthy margins.

Post-operative care involves packing the surgical site loosely with an antiseptic- or antibiotic-soaked sponge and bandaging the foot with a diaper and duct tape. The surgical site is inspected daily, and any questionable devitalized tissue is debrided. Systemic antibiotics are indicated in many cases, but many horses recover without antibiotics. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (e.g., phenylbutazone, 2.2-4.4 mg/kg, q 12 h) are indicated to minimize inflammation and encourage weight bearing. In most cases, healing is usually complete in 8-12 wk.

Affected horses have an excellent prognosis for return to athletic function unless laminitis is the underlying cause of the phalangeal infection.

|

| Fig. 2. Radiographic examination of a foot of a horse that presented with a recurrent sole abscess and a draining tract that extended to the ventral surface of the distal phalanx. A sequestrum that requires surgical removal and debridement for resolution of the lameness is apparent. |

|

| Fig. 3. Compression of the digital vessels against the proximal sesamoid bones with a Vetrap tourniquet will greatly facilitate visualization during surgery. Twisting the Vetrap 180° over the digital vessels will aid in the compression of the vessel walls. |

|

| Fig. 4. Identification of a semicircular radiolucent defect at the dorsolateral margin of distal phalanx is usually definitive for the presence of a keratoma. |

5. Keratomas

A keratoma is a benign, keratin-containing soft-tissue mass that develops between the hoof wall and the distal phalanx. The etiology is unknown but may be a response to chronic irritation.

The clinical signs are those of a progressively developing lameness that becomes more pronounced as the keratoma gradually enlarges and creates pressure between the hoof wall and distal phalanx. The lameness may be intermittent. As the keratoma enlarges, disruption of the external hoof architecture may become apparent as evidenced by a bulge in the hoof wall or inward deviation of white line.

The diagnosis is definitively confirmed when radiography of the digit reveals a semicircular or circular radiolucent defect at margin of the distal phalanx. This radiographic lesion is the result of the expanding keratoma that causes focal bone resorption. The bone margin surrounding the keratoma is smooth and not sclerotic, which differentiates a keratoma from an infection.

Surgery is indicated when the lameness is confirmed to originate in the foot using diagnostic blocks and the pathogpneumonic radiographic lesion is identified. The keratoma is approached by resecting the hoof capsule overlying the mass. The most difficult aspect of surgery is targeting the precise location in which to enter the hoof wall. This is best accomplished by taping radiopaque markers to the hoof wall and obtaining sequential radiographs to ascertain the location. A trephine or motorized burr is used to remove the hoof wall overlying the keratoma. Either method is less invasive than the hoof-wall resection technique previously used, and both preserve the stability of the hoof wall during the convalescent period.

Surgery can be performed in the anesthetized horse or the standing horse anesthetized locally. The authors prefer the standing approach for most horses, unless their temperament precludes this choice. Again, a tourniquet is employed to reduce hemorrhage and aid visualization.

Postoperatively, a foot bandage is applied and changed at 3-4 day intervals until the resected defect in the hoof wall has cornified. After granulation tissue has covered the exposed bone, astringents such as merthiolate (thiamersol) or iodine (2-7%) are applied to dry the tissue and enhance cornification. Phenylbutazone is administered as needed in the post-operative period. Antibiotics are generally unnecessary, because infection does not typically accompany the keratoma.

6. Necrosis of the Collateral Cartilage

Infection and necrosis of the collateral cartilage can be seen as a sequelae to lacerations, foot abscesses, puncture wounds, gravel (chronic ascending infection under hoof wall), hoof cracks, and blunt trauma (over-reach injuries, kicking inanimate objects), all of which result in avascular necrosis.

Affected horses become lame when abscesses form within the cartilage. The lameness is often intermittent, ranging from mild when the abscesses are draining to the exterior to severe when the draining tracts seal for a period of time. When the infection becomes established, marked soft-tissue swelling over affected cartilage becomes apparent. Purulent drainage from the cartilage may or may not be present at the initial exam depending on the patency of the draining tract.

The diagnosis is made by observation of draining tracts proximal to the coronary band over the affected cartilage. Radiographs obtained with a flexible metal probe in the tract or after infusion of contrast media into the tract will help determine the depth of the tract and confirm involvement of the cartilage. Most importantly, if the abscesses within the cartilage are draining at presentation, the horse may not be extremely lame. This should not delay surgery, because lameness will recur when the draining tracts seal again. Because the cartilage is relatively avascular, antibiotics and infusion of caustic agents into the draining tracts is usually ineffective in resolving the infection.

|

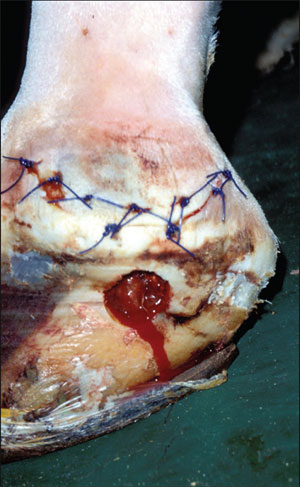

| Fig. 5. Post-operative photograph at bandage change 2 days after removal of an infected collateral cartilage. A curvilinear incision, based proximally, was created to access the diseased cartilage proximal to the coronary band. Diseased cartilage distal to the coronary band was accessed through the trephine hole in the hoof wall. |

Surgery is indicated based on the presence of a swollen cartilage with draining tracts. Treatment is aimed at excision of the affected portions of cartilage and overlying soft tissue and establishment of ventral drainage. The surgery is accomplished with the horse in lateral recumbency. As with other foot procedures, a tourniquet is applied to enhance visualization during surgery. In addition, regional perfusion of the distal limb can be performed while the tourniquet is in place. Only the infected portions of the collateral cartilage need to be excised. During the surgical procedure, the foot is extended in an attempt to tense the palmar pouch of the distal interphalangeal joint and retract it from the deeper areas of dissection. The authors prefer to access the proximal portion of cartilage above the coronary band through a curved incision based proximally. This technique preserves skin for primary closure and allows easier access to portions of the cartilage that will be accessed through the hoof wall later in the procedure. The skin flap is reflected proximally, and all accessible diseased proximal cartilage is removed. Diseased cartilage beneath and distal to the coronary band is removed through a trephine hole in the hoof wall. The tissue and cartilage between the trephine hole and proximal incision is removed by sharp dissection to allow for ventral drainage. If the diseased tissue extends axially toward the joint, the integrity of the joint can be assessed using arthrocentesis and distention of the distal interphalangeal joint at a site remote from the surgical incision. At the completion of surgery, the skin incision is sutured, and the trephine hole is packed loosely with gauze sponges. The foot is bandaged until the skin incision is healed and the trephine hole is cornified. Systemic antibiotics are generally indicated for 7-10 days. Additionally, regional perfusion of the distal limb should be considered in cases where diseased tissue extends down to the region of the distal interphalangeal joint in a location that would risk penetration of the joint capsule with overzealous debridement.

The prognosis is good after complete resection of the diseased cartilage and soft tissue. Incomplete resection, however, may be complicated by recurrence of clinical signs and necessitate reoperation.

7. Conclusion

Because of the hoof capsule, surgery of the equine foot is often perceived to be quite difficult. Knowledge of the specific diseases that require surgical intervention as well as an in-depth understanding of the anatomy of the tissues beneath the hoof capsule is a prerequisite to successful surgical treatment. The surgical principles used to treat the conditions outlined can be applied to a variety of other conditions for which access through the hoof wall is required (Fig. 1-5).